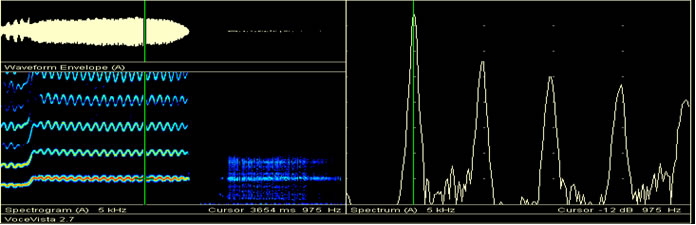

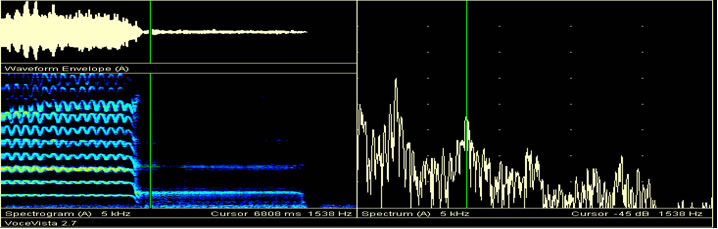

Figure 1. A professional soprano singing B5, then using vocal fry (lower right corner of the spectrogram) to highlight the

location of vowel formants. Note the close proximity of the fundamental to the first formant.

Vowel Modification Revisited

John Nix

In the last 40 years, many vocal pedagogy authors have written about the need for appropriate vowel modification. Modification involves shading vowels with respect to the location of vowel formants, so that the sung pitch or one of its harmonics receives an acoustical boost by being near a formant. The goals of such modification include a unified quality throughout the entire range, smoother transitions between registers, enhanced dynamic range and control and improved intelligibility. Elite singers, whether they consciously recognize they are modifying vowels or not, become experts at making subtle changes in vowels as they sing, or they do not have consistent careers. Modification concepts which have been widely accepted are summarized below:

Figure 1. A professional soprano singing B5, then using vocal

fry (lower right corner of the spectrogram) to highlight the

location of vowel formants. Note the close proximity of the fundamental to the

first formant.

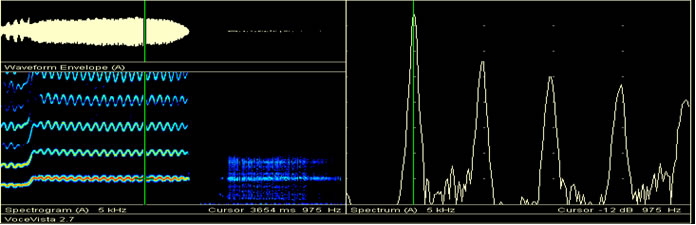

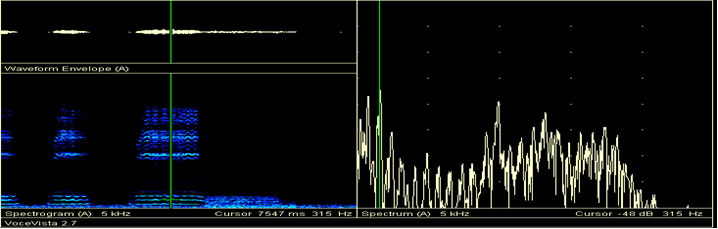

Figure 2. The author singing the vowel [i] on Eb3. Note the

strength in the second harmonic (H2) at 315 Hz

(close to the first formant) and the twelfth harmonic (H12) at approximately

2000 Hz

(in close proximity to the second formant).

Other information now needs to be integrated into pedagogical approaches. Three areas of continuing study have particular significance for singing teachers.

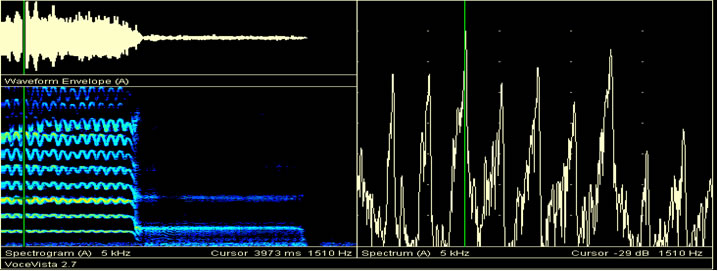

Figure 3: Vocal fold vibrational amplitude change as a function

of fundamental frequency, due to subglottal

pressure variations in the vocal fold driving pressure. From Titze, Principles

of Voice Production.

Used with permission.

The implication of subglottal resonances for singers is that at some pitches, particularly around D3 and D4, pressures due to subglottal resonances increase the amplitude of the vibration of the vocal folds, while at other pitches, especially around G#3 and C5, subglottal resonance factors decrease the amplitude of vocal fold vibration. Titze suggests that this change in vocal fold vibration can be controlled by adjusting vocal fold adduction slightly. When subglottal driving pressures substantially increase vocal fold vibration amplitude, a slight increase is abduction may be warranted to prevent overdriving the system; when subglottal driving pressures substantially decrease vibration amplitude, a slight increase in adduction may be helpful. By doing so, the singer may avoid large changes in intensity from one pitch area to another.

How might singers and teachers apply this information to singing repertoire? Here are a few examples:

Baritone: “Bella siccome un angelo,” Don Pasquale, sustained final note of the cadenza on the word “cor” on the pitch Db4 (277 Hz).

Subglottal driving pressures are highly positive at this pitch level, approaching their maximum. And, as this note is below the passaggio, optimal vocal tract resonance tuning involves tuning the second harmonic (H2, at 554 Hz) to slightly below the first formant (F1) of a vowel.

Recommendations:

Soprano: “Steal me, sweet thief,” The Old Maid and the Thief, climatic high note on “steal” on Bb5 (932 Hz)

Subglottal driving pressures are negligible or slightly positive at this pitch range. Optimal vocal tract resonance in the female high voice involves tuning the fundamental frequency (i.e. the sung pitch) to slightly below the first formant; however, with the fundamental so high at 932 Hz, the [i] vowel in the word “steal” is not appropriate, with its first formant at approximately 370 Hz. In fact, no speech production vowel has a first formant at 932 Hz. The closest vowels are [æ] at approximately 770 Hz and [a] at approximately 890 Hz. This pitch is around the upper limit of where the sung pitch and the first formant can be tuned to each other.

Recommendations:

Tenor: “Il mio tesoro,” Don Giovanni, sustained notes on “vado” on F4 (349 Hz)

Subglottal driving pressures are slightly positive to negligible. Between D4 and C5, subglottal driving pressures shift from maximally increasing vibrational amplitude to maximally decreasing it. Depending on the tessitura of the singer, the note can be sung “open” or “covered.”

Recommendations:

As always, each singer is unique. Fine adjustments for slight individual differences and how to best teach these concepts are left up to the teacher and the performer. Some singers prefer objective visual feedback about vowel tuning by using a spectrum analysis program like Voce Vista or Gram in the studio or the practice room; others respond best to verbal suggestions of target vowels to sing; some others thrive on kinesthetic commands like “adjust the space or lift of that vowel a bit more for the pitch and power of that note;” and still other singers find demonstration/imitation or imagery most effective. Chacun à son gout! And, as always, optimal sound output must constantly be weighed against the need for intelligibility. In almost every case, however, optimal acoustical tuning will both aid ease of production and improve intelligibility.

For further reading on this subject, readers may wish to consult the following sources:

Austin, Stephen F. and Titze, Ingo R. “The Effect of Subglottal Resonance Upon Vocal Fold Vibration,” Journal of Voice 1997; 11:4, 391-402.

Baken, R. J. and Orlikoff, Robert F. Clinical Measurement of Speech and Voice. 2nd edition. San Diego: Singular Press, 2000.

Miller, Donald G. and Schutte, Harm K. “Toward a Definition of Male ‘Head’ Register, Passaggio, and ‘Cover’ in Western Operatic Singing,” Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica 1994; 46: 157-170.

Schutte, Harm K. “The Effect of F0/F1 Coincidence in Soprano High Notes on Pressure at the Glottis,” Journal of Phonetics 1986; 14: 385-392.

Titze, Ingo R. “A Theoretical Study of F0-F1 Interaction with Application to Resonant Speaking and Singing Voice,” Journal of Voice, in press.

Titze, Ingo R. Principles of Voice Production. Iowa City, IA: National Center for Voice and Speech, 2000.

Titze, Ingo R., Mapes, Sharyn, and Story, Brad. “Acoustics of the Tenor

High Voice,” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1994;

95:2, 1133-1142.